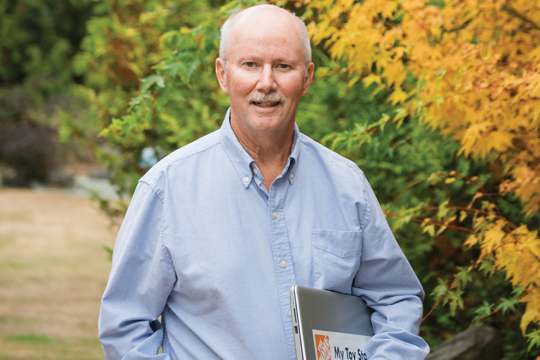

Doug Runchey worked at Home Depot after retiring from the public service, but then he discovered some niche knowledge that would allow him to work for himself, advising others about working in retirement. Photo by Karen McKinnon

When Doug Runchey retired at age 50 after working with the federal government for 33 years, he knew his working life was far from over.

So the Vancouver Island man got a job with retailer Home Depot and was soon peppered with questions by other retirees and seniors. Having worked in the Income Security Programs branch of Human Resources and Skills Development Canada as a specialist in the Canada Pension Plan (CPP) and Old Age Security (OAS), Runchey knew his way around the rules and regulations, which he was often called upon to share in his new, semi-retired status.

Eventually he launched DR Pensions Consulting, which provides pension advice, including detailed calculations for CPP retirement planning. Often his focus is on helping people figure out what they can get from the federal pension and when. Then there’s the additional calculation of what happens when someone is already collecting CPP and then goes back to work after age 65.

Runchey, who has been a member of Federal Retirees since 2005, has observed that people are living longer and seniors seem to be healthier and much more active than they once were. He, for example, is “happily semi-retired” at age 69.

“It used to mean, from my experience, that when someone reaches retirement age, that was the end of their working life,” says Runchey, a Federal Retiree who lives in B.C.’s Comox Valley.

Now people are slowly testing the retirement waters, taking on a new career in retirement or picking up another job after having retired.

This new, sometimes unanticipated status, presents another income-generating opportunity apart from the salary. Those 65 and older who are working have the choice of continuing to pay into CPP or the Quebec Pension Plan (QPP) to tap into the programs’ post-retirement benefit, even if they’ve already started collecting it.

“I believe there’s a benefit in continuing to contribute to CPP if you’re over 65 because you’ll get these post-retirement benefits. And these post-retirement benefits are just going to increase the amount of CPP you get every year,” says Willis Langford, a fee-only retirement income planner in Calgary who specializes in what he calls de-accumulation, which is looking for stable income through the tax-efficient draw down of assets in retirement.

“Your employer would prefer you don’t, because then they don’t have to make their equal contribution to the plan.”

The post-retirement benefit starts appearing in monthly CPP/QPP payments the following year in July for those who have started collecting CPP/QPP, even if they continue to work. The post-retirement benefits are automatically added to the monthly CPP/QPP benefit payments for those enrolled in CPP/QPP, as long as they file their income tax return every year.

The first $3,500 of earnings doesn’t qualify. So those who are just picking up small jobs won’t have the option of making CPP/QPP payments on those earnings.

For those who choose to continue paying into CPP/QPP, the post-retirement benefit could add 2.5 per cent to the monthly CPP payment for a total of about $340 per year. The benefits are similar for those who live in Quebec. While the amount it adds to the government pension cheque every month doesn’t appear to be significant, Langford believes the benefits of continuing to make the CPP/QPP contributions in retirement far outweigh the option of not contributing because the contributions are matched by the employer.

But working in retirement doesn’t always mean working for someone else. B.C.’s Runchey points to his own situation. Being self-employed means he would have to pay both the employee’s and the employer’s portion, so the post-retirement benefit is simply not worth his while.

Working in retirement includes other risks that retirees may consider before signing onto a new vocation. The additional income from that job may well push an individual into another tax bracket, when added to any private pension plans, CPP/QPP and other possible sources of income. The risk, in addition to paying more taxes, is having OAS clawed back.

When a retiree’s salary exceeds $81,761, OAS is reduced by 15 per cent. It’s gradually eroded as the salary increases. It could be lost altogether if the income reaches the maximum threshold, which is currently $134,626. That can be mitigated with contributions to an RRSP, but only to age 71.

Another consideration is the over- age-65 tax credit that has a $39,000 threshold, which diminishes when the income exceeds that amount.

“They have to be careful of not working too much to just end up losing more OAS… they kind of have to make sure they’re managing their total income,” Langford says.

Large taxable gains that can be derived from big transactions such as from selling a rental property or a business require advance planning. There’s no point in signing up for OAS and then selling income property and realizing capital gains soon after because OAS will be clawed back. “Every action you take has an impact on some other part of your finances. But if you plan in advance, then you can prevent some of these mistakes and costs and loss of benefits,” Langford says.

David Wagener began weighing his options as a federal game warden in Ontario long before retiring to the family farm in New Brunswick two years ago. But last May, he took on a job as a night watchman, working three 15-hour shifts per week in a mill that is being revived from a decade-old dormancy under new ownership.

Now 66, Wagener knows he’s going to take some hits. He’ll be paying more income tax and then there’s the consideration of some impact upon his OAS. Just the same, he believes it’s worth it.

“I love it,” he says. “It’s a pretty peaceful job. I get to watch the wildlife. It gives my life some structure. I appreciate my days off more.”

And that’s the thing, explains Quebec retirement planning educator Simon Houle of ÉducÉpargne, a government-funded organization focusing on good savings habits. Mental health in retirement and retirement planning are often overshadowed by a focus on finances. Houle sees that the growing trend of phasing into retirement offers retirees a taste of retirement while also continuing to get fulfilment out of their job and provides that very important sense of purpose, as does working in retirement.

The psychological aspects of retirement, he adds, are gradually getting more attention as continuing education for financial planners increasingly focuses on behavioural finance.

“Most people just think about the money, but you need to be happy,” Houle says. “Having purpose in life is super important to everybody. A lot of people when they reach retirement, if their kids are gone, don’t really have a purpose. For a lot of people their purpose is their job. And if they’re able to keep on working, it’s a good thing for them.”